68 - Classical

Reflecting on Virgil, C. Day Lewis, and transmitting the ancient tradition, alongside a Sports Report on South Africa's World Test triumph, and a review of Andor 2.9-12

Classical

“The moon herself has made some days in varying degrees

Lucky for work. Beware of the fifth: that is the birthday

Of Hell’s pale king and the Furies; then earth spawned an unspeakable

Brood of titans and kings, gave birth to the ogre Typhoeus

And the brothers who leagued themselves to hack the heavens down:

Three times they tried, three times, to pile Ossa on Pelion –

Yes, and to roll up leafy Olympus on Ossa’s summit;

And thrice our Father dislodged the heaped-up hills with a thunderbolt.”

-from “Georgic I” by Virgil, translated by C. Day Lewis

I am teaching ancient history a lot right now – one client is a British student, the other an agency providing English-language tuition to overseas students. You can offer cliches (true cliches, even) about the universality of the classics, of the old stories. That doesn’t touch on the – let’s call it inculturation necessary in teaching the period and its stories.

This is especially obvious to me with the overseas students, speaking in a second language about texts in a third language and cultures neither of us directly stem from. Not only are there cultural and political sensitivities to account for – and in fact there are with British students, too – but there is the matter of communicating a “common tradition” in circumstances where it might, in fact, not be really common.

For the former issue, just take the wide array of political arrangements on offer in Classical and Hellenistic Greece, especially if you include the late New Kingdom and Persia. You have democracy, aristocratic oligarchy, constitutional monarchy based upon a military elite and a vast slave class, god-emperors, and autocrats of rather humbler claim. As I say, the generic British student copes about as badly with this range as any foreigner; the Kazakhstani may recoil at the participatory assemblies with real power, the American may gasp at the idea of an aristocratic elite reliant on a large slave caste, but the Briton is as liable to be bothered by each as much as the next.

For the latter issue, just take C. Day Lewis’ perfectly viable efforts with the first Georgic. It was translated for reading on radio; he uses a loose fourteener line with some inspiration from folk songs, and aims to translate line-for-line from the original. The fourteener gives him space to expand out the compacter Latin hexameter, and he is a lyric enough poet by instinct to usually find happy analogues for the sensuous array of natural simile and observation in the Georgics.

Here, though, we move from an observation of nature and its connection to the human cycle – observe the days of the moon cycle, learn from them – and end up at a brief retelling of myth. This is, of course, prevalent across all Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, Golden Age, Silver Age, and Late Antique poetry and indeed literary writing more generally. The habit of mind which connects any topic whatsoever to the great mythical substructure is universal in Antiquity. I suspect it is universal now, if with different myths.

How to translate or teach this? Well, Day Lewis takes the simpler route, given his choice of literalism – here we just have the resonant list of names, the constant allusion and micro-narrative. It is no great pain, really, with a modern paperback’s endnotes and access to Google, to work all this out yourself, and the research is a healthy habit anyway. Yet we must admit at first it is fairly impenetrable. What must you know to successfully parse the whole for facial meaning?

The moon cycle. The God of the Underworld and the Kindly Ones. Something about Typhoeus, and then the whole unnamed and elliptical plot of Otus and Ephialtes to reach heaven by piling mountains on top of each other.

Not so hard as many such passages, but Virgil here trades on an informed audience, and on a wider storytelling tradition. Now the teacher expects neither. Do you choose comparisons in modern mythology? How does that work across culture (to a foreign student online, to a Mirpuri teen in the old East End, to wholly denatured TikTok teens in a state secondary)? Which mythology? How apposite are the comparisons? Or if – and this is usually safer – you attempt to present the history or the myth on its own merits, in its own terms, how do you make progress across the great gulf of different understandings?

This is perhaps all simply observing the challenge any teacher, and any translator, faces at any time. Yet it is particularly pointed for me right now. Teaching history regularly reminds me of the loss of shared traditions and culture; there is a tidal ebb away from what was widely shared, as well as to some degree a new and unexamined shared tradition. Yet of course it is precisely the teaching of history that can offer that examination: history is not a simple matrix to map our experiences on, but a strange and different world that highlights how equally strange our world is. History also offers a functionally infinite array of points of comparison and reflection – as I saw someone point out regarding foreign policy decisions, we must realize that there are other points in history than 1938 and 2003.

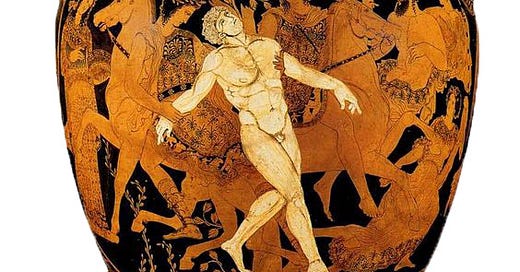

I should close by saying that, ultimately, The Kids Are Often Alright. Though we do not have the ready recognition of Virgil’s allusions that Maecenas would have, and so this one specific passage may be particularly opaque to us – how often the facility and purpose of an ancient text is totally obscured to us! – we are still humans, and even this past week one of my overseas students still thrilled to the tale of the Argo and to the old vase with Medea hexing the Talos. The tradition can, when transmitted as living fire, still find new hosts.

Sports Report – It’s Good That South Africa Won, I Guess?

I am glad that South Africa won the final of the World Test Championship. I think it demonstrated the general tightness of the contest through the first three-quarters proved the merits and excitement of good Test cricket; I think South Africa winning is a fine reminder that this is a sport for the world, not the so-called Big Three. I like Temba Bavuma, as a Durham supporter I really like David Bedingham, and there is no doubt that Kagiso Rabada is one of the best quick bowlers ever.

Yet their victory highlights two troubling things.

The first – the political, let us say – is for me less important when it comes to enjoying the sport. I can put clear water between the side on a pitch and the politics behind it. Sport, like visual arts and music, is of course not wholly separable from politics – but the creative and athletic gifts and accomplishments themselves transcend or even subsume the politics. Lovecraft’s rather strange racial anxieties inspired great depictions of deeper and more universal human anxieties. Lead turned to gold – that’s the alchemy of these disciplines, turning the merely human, and often poorly human, into something sublime. (But don’t tell Cole Palmer any of this, for he will not understand; in his case intense stupidity has combined with preternatural gifts to produce a wholly focussed footballing Zen master.)

Nonetheless, in South Africa’s case it is worth remembering that they field racially quotaed teams, and in most cases this quota system has been to the active detriment of the team and to the national system. A victory by a team led by Bavuma and spearheaded by Rabada is scarcely positive evidence of the success of the quota system, at least at the national level. The quota system has generally weakened the side and encouraged very good players to seek overseas qualification and franchise contracts (and the former Kolpak status) instead of committing to national cricket. Moreover, I cannot shake from my mind the recent statement of the senior ANC leader when asked whether he intended to commit genocide upon the remaining South African whites: “Not yet” was the comforting answer.

Nevertheless, I do not set aside the magnificent achievements of the last pre-ban Apartheid South African teams, and so I will not set aside the fine achievement of this South African team.

That achievement, though, must be balanced by a recognition of the change in the game: South Africa fielded a pretty undistinguished batting lineup: averages 36.50, 37.52, 22.21, 30.00, 35.55, 31.67, and 38.22. There is an irony that Bavuma, the skipper, now holds the highest average, and has had a fine few years with the bat – for a long time he was, bluntly, obviously a quota hire, and his success is a reminder that unjust systems produce magnificence at times that surprise us. (Whether or not it was unjust, I remind the audience that Britain’s best period of governance was one depending on inherited wealth as the basis of political activity.)

South Africa beat Australia, who are not the Australia of years past, either, but it must be granted that they look better on paper. Five of the top seven bats average over 44; one (Smith) is an all-time great, averaging 56 and change. Nonetheless, the Australian lineup suffers from the same brittle bone disease every modern lineup does, prone to much more dramatic swings in performance, vulnerable to collapse. Ultimately, though, their downfall was the inability of their excellent attack to defend a comparatively high target (282). Hazlewood (281 wickets @ 24.70), Lyon (552 wickets @ 30.33), Starc (387 wickets @ 27.49), and Cummins (3031 @ 22.20) are an all-time attack, even if there are signs of fading power, and it is a genuinely fine accomplishment by Bavuma and co to conquer them.

Nevertheless, this is a bowler’s era, and averages reflect that; the loss of technique and focus connected with the massive shifts in the game’s formats and who plays what are visible even at a glance at the numbers, let alone digging through the deeper stats and looking at the scorecards and watching the matches. Cummins and Rabada are greats, no doubt, who would succeed in any era – but it is no harm to their records that they are facing shoot-from-the-hip lineups across the world.

I suppose I am also worried that, really, it doesn’t matter that South Africa have won this odd and not really economically significant title. (Or only economically significant in the terms of the argument Richard Gould has rightly made about keeping it at Lord’s every time: in England it will always sell out, which it won’t elsewhere. I suppose maybe in Australia.) So long as the broadcast money for Tests really only cashes out big for the Big Three and then usually against each other, the shift in the game can only continue, and speed up.

Andor, Season 2, Episodes 10 to 12

A fitting final batch, which instead of focussing on grand events – you got a little of that in episode 8, with Mon’s speech – looks instead at Luthen Rael, the people he chose and who chose him, and the endless corrosion that lawless tyranny works upon its subjects.

Luthen is the opposite of the tyrant, we discover in episode 11 – through Kleya’s flashbacks, a usually trite device used here for the first time I think since Cassian’s early season 1 flashbacks – because he had what amounts to a nervous break as his Imperial Army unit performed a massacre. In Generation Tech’s words, at this point he suffered “total ego death”. Palpatine is pure egoism, a pure cult of the self gradually worming its way into every crack in society – ably represented by Director Orson Krennic of the ISB and Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin of the Governorate and Admiral Motti of the Navy, when zoomed out at the high level, and ultimately by Supervor Meero at the microscopic. Palpatine – Palpatinism – is a cult of the self, of ultimate self-agency, where everyone longs to have the most power (over self, over others) possible. Palpatinism accepts no restraints; in this way, it totally destroys freedom.

Luthen Rael does not exist for himself. He exists for a girl he saved from the massacre: a daughter unsought, but his salvation at that moment of despair. That daughter, that idea of a future, of irreducible duties to another, leads him to do more than every idealist in the galaxy: through deceit, terrorism, murder, and – even worse – politics, he orchestrates the foundation of the Rebel Alliance.

Mon has a daughter, but the best she can do is a fairly self-indulgent offer of cancelling the arranged marriage at the very last moment; that whole wedding passage is one about Mon ignoring realities, and not very appealing. Maarva Andor realizes, almost too late, that for her adoptive son and for her people she has to speak out – and Providence provides an opportunity beyond death. Luthen Rael dies a sort of personality death, and the reversal of his name (Lear à Rael) shows the essence of the matter. He never indulges himself; he keeps himself in the place of danger right up until the decisive moment, and at that point, as if with the power of premonition, sends Kleya away.

Dedra comes to confront him, high in her pride. She was “rescued” from her orphan life by Palpatine’s Kinderblock, and taught to place her own desires first, channelled through and excused by an omnicompetent bureaucracy. Mrs Karn was, perversely, right: Dedra really did lack the love of a mother, or at any rate a parent. Kleya was rescued from the massacre by a flesh-and-blood human being, and even if he wasn’t demonstrative, wasn’t open, he still taught her about love and human connection.

The galaxy is, I suppose, saved by Cassian’s decision to go against orders and steal a ship to respond to “Luthen’s” hail, knowing it might be a trap. More importantly, Kleya is saved: Cassian comes because he trusts Luthen, believes in Luthen, and Melshi comes (and it is vital that he comes, he’s the only one to dodge the flashbang) because Cassian asks him to come. Melshi is alive because Kino Loy, who could not swim, decided to rescue everyone who could. The communication from Kleya comes through because Wilmon receives it; Wilmon is on Yavin, not with Saw, because he met Dreena on Ghorman. Saw, meanwhile, has a Star Destroyer over his head because he has lost all human connection. Human connection, hand-over-hand, is the mark of the Rebellion – no, the Alliance to Restore the Republic. It is revolutionary in the older, not the newer sense. It is a returning. The totalitarian state, enabled by dark science and advanced technology, crumbles in the face of such a revolution, despite winning every battle along the way.

This is surely what Partagaz realizes as he listens to Nemik’s Manifesto, as he awaits arrest. “The Imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. . . the day will come when all these skirmishes and battles, these moments of defiance will have flooded the banks of the Empire’s authority and then there will be one too many. One single thing will break the siege.” Partagaz, perhaps, is a Guthrum without an Alfred: a man wise enough to know something wiser than he. Even there, though, in the heart of the ISB, in the heart of the Total State, if there is not an Alfred, there is a small miracle: Lagret, a man who has displayed no egoism or ambition, is sent to arrest Partagaz. Partagaz asks him to leave for a moment so he can gather himself. A long look is shared. Lagret leaves, the door shuts – and Lagret turns to face the two Stormtroopers (not ISB personnel). He stands a lonely guard in the face, as it were, of Palpatine himself, of the very symbol of his power. The inevitable shot is heard, and Lagret directs the Stormtroopers to wait, as he bows his head in memoriam.

The Imperial need for control is unnatural. The ISB itself cannot maintain control over its own people. Lagret saves a friend from torture and degradation. Lonnie Jung joins Luthen in sacrificing everything of his own for a cause he knows is right; he puts his family at one kind of risk because he knows a greater risk faces them if he does not. Dedra falls for Syril, and risks operational security for him (but his conscience is too untainted, as lamed as he is by the Total State); she has just enough rebellion in her, if only as a result of her ego, that she follows the money, and her files end up with the three key words: Jedha. Kyber. Erso.

Galen Erso. Another man who plays out a long and secret game against the Empire for the sake of his child.

The Total State hates the family because the Total State is a parody and perversion of the family. Star Wars, rather against expectation, teaches us that the family is the doom of the Total State.

Even Bix’s breaking up of her family – taking Cassian’s child away – is a recognition of this. Their child must be safe; their child can only be safe if the Empire falls, and for the Empire to fall, Cassian must be able to fight it. Cassian Andor’s child dooms the Empire.

Luthen Rael. Galen Erso. Owen Lars. Bail Organa. Anakin Skywalker. Star Wars is a story of fathers sacrificing for their children, and that sacrifice turning out to be for the freedom of everybody else’s children, too.